It turns out that finite state machines are useful for things other than expressing computation. Finite state machines can also be used to compactly represent ordered sets or maps of strings that can be searched very quickly.

In this article, I will teach you about finite state machines as a data

structure for representing ordered sets and maps. This includes introducing

an implementation written in Rust called the

fst crate.

It comes with

complete API documentation.

I will also show you how to build them using a simple command line tool.

Finally, I will discuss a few experiments culminating in indexing over

1,600,000,000 URLs (134 GB) from the

July 2015 Common Crawl Archive.

The technique presented in this article is also how Lucene represents a part of its inverted index.

Along the way, we will talk about memory maps, automaton intersection with regular expressions, fuzzy searching with Levenshtein distance and streaming set operations.

Target audience: Some familiarity with programming and fundamental data structures. No experience with automata theory or Rust is required.

Teaser

As a teaser to show where we’re headed, let’s take a quick look at an example.

We won’t look at 1,600,000,000 strings quite yet. Instead, consider ~16,000,000

Wikipedia article titles (384 MB). Here’s how to index them:

$ time fst set --sorted wiki-titles wiki-titles.fst

real 0m18.310The resulting index, wiki-titles.fst, is 157 MB. By comparison, gzip

takes 12 seconds and compresses to 91 MB. (For some data sets, our indexing

scheme can beat gzip in both speed and compression ratio.)

However, here’s something gzip cannot do: quickly find all article titles

starting with Homer the:

$ time fst grep wiki-titles.fst 'Homer the.*'

Homer the Clown

Homer the Father

Homer the Great

Homer the Happy Ghost

Homer the Heretic

Homer the Moe

Homer the Smithers

...

real 0m0.023sBy comparison, grep takes 0.3 seconds on the original uncompressed data.

And finally, for something that even grep cannot do: quickly find all article

titles within a certain edit distance of Homer Simpson:

$ time fst fuzzy wiki-titles.fst --distance 2 'Homer Simpson'

Home Simpson

Homer J Simpson

Homer Simpson

Homer Simpsons

Homer simpson

Homer simpsons

Hope Simpson

Roger Simpson

real 0m0.094sThis article is quite long, so if you only came for the fan fare, then you may skip straight to the section where we index 1,600,000,000 keys.

Table of Contents

This article is pretty long, so I’ve put together a table of contents in case you want to skip around.

The first section discusses finite state machines and their use as data structures in the abstract. This section is meant to give you a mental model with which to reason about the data structure. There is no code in this section.

The second section takes the abstraction developed in the first section and

demonstrates it with an implementation. This section is mostly intended to

be an overview of how to use my fst

library. This section contains code. We will discuss some implementation

details, but will avoid the weeds. It is okay to skip this section if you don’t

care about the code and instead only want to see experiments on real data.

The third and final section demonstrates use of a simple command line tool to build indexes. We will look at some real data sets and attempt to reason about the performance of finite state machines as a data structure.

- Finite state machines as data structures

- The FST library

- The FST command line tool

- Lessons and trade offs

- Conclusion

Finite state machines as data structures

A finite state machine (FSM) is a collection of states and a collection of transitions that move from one state to the next. One state is marked as the start state and zero or more states are marked as final states. An FSM is always in exactly one state at a time.

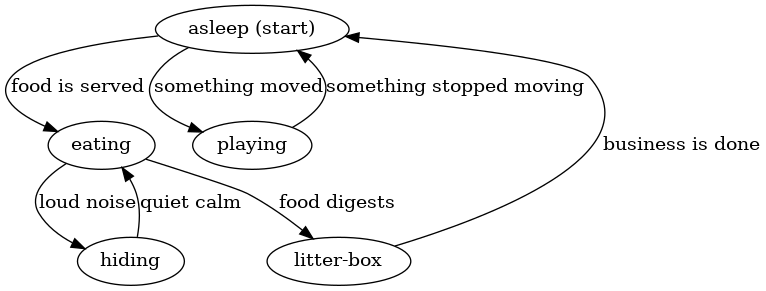

FSM’s are rather general and can be used to model a number of processes. For example, consider an approximation of the daily life of my cat Cauchy:

Some states are “asleep” or “eating” and some transitions are “food is served” or “something moved.” There aren’t any final states here because that would be unnecessarily morbid!

Notice that the FSM approximates our notion of reality. Cauchy cannot be both playing and asleep at the same time, so it satisfies our condition that the machine is only ever in one state at a time. Also, notice that transitioning from one state to the next only requires a single input from the environment. Namely, being “asleep” carries no memory of whether it was caused by getting tired from playing or from being satisfied after a meal. Regardless of how Cauchy fell asleep, he will always wake up if he hears something moving or if the dinner bell rings.

Cauchy’s finite state machine can perform computation given a sequence of inputs. For example, consider the following inputs:

- food is served

- loud noise

- quiet calm

- food digests

If we apply these inputs to the machine above, then Cauchy will move through the following states in order: “asleep,” “eating,” “hiding,” “eating,” “litter box.” Therefore, if we observed that food was served, followed by a loud noise, followed by quiet calm and finally by Cauchy’s digestion, then we could conclude that Cauchy was currently in the litter box.

This particularly silly example demonstrates how general finite state machines truly are. For our purposes, we will need to place a few restrictions on the type of finite state machine we use to implement our ordered set and map data structures.

Ordered sets

An ordered set is like a normal set, except the keys in the set are ordered. That is, an ordered set provides ordered iteration over its keys. Typically, an ordered set is implemented with a binary search tree or a btree, and an unordered set is implemented with a hash table. In our case, we will look at an implementation that uses a deterministic acyclic finite state acceptor (abbreviated FSA).

A deterministic acyclic finite state acceptor is a finite state machine that is:

- Deterministic. This means that at any given state, there is at most one transition that can be traversed for any input.

- Acyclic. This means that it is impossible to visit a state that has already been visited.

- An acceptor. This means that the finite state machine “accepts” a particular sequence of inputs if and only if it is in a “final” state at the end of the sequence of inputs. (This criterion, unlike the former two, will change when we look at ordered maps in the next section.)

How can we use these properties to represent a set? The trick is to store the keys of the set in the transitions of the machine. This way, given a sequence of inputs (i.e., characters), we can tell whether the key is in the set based on whether evaluating the FSA ends in a final state.

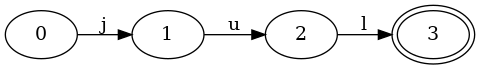

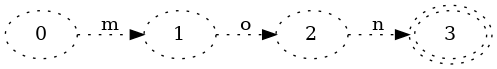

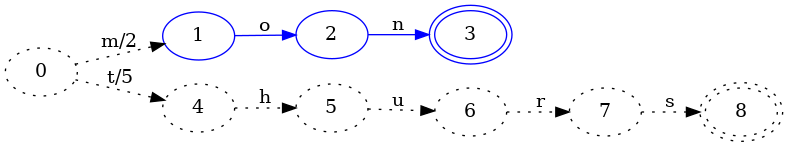

Consider a set with one key “jul.” The FSA looks like this:

Consider what happens if we ask the FSA if it contains the key “jul.” We need to process the characters in order:

- Given

j, the FSA moves from the start state0to1. - Given

u, the FSA moves from1to2. - Given

l, the FSA moves from2to3.

Since all members of the key have been fed to the FSA, we can now ask: is the

FSA in a final state? It is (notice the double circle around state 3), so we

can say that jul is in the set.

Consider what happens when we test a key that is not in the set. For example,

jun:

- Given

j, the FSA moves from the start state0to1. - Given

u, the FSA moves from1to2. - Given

n, the FSA cannot move. Processing stops.

The FSA cannot move because the only transition out of state 2 is l,

but the current input is n. Since l != n, the FSA cannot follow that

transition. As soon as the FSA cannot move given an input, it can conclude that

the key is not in the set. There’s no need to process the input further.

Consider another key, ju:

- Given

j, the FSA moves from the start state0to1. - Given

u, the FSA moves from1to2.

In this case, the entire input is exhausted and the FSA is in state 2. To

determine whether ju is in the set, it must ask whether 2 is a final state

or not. Since it is not, it can report that the ju key is not in the set.

It is worth pointing out here that the number of steps required to confirm whether a key is in the set or not is bounded by the number of characters in the key! That is, the time it takes to lookup a key is not related at all to the size of the set.

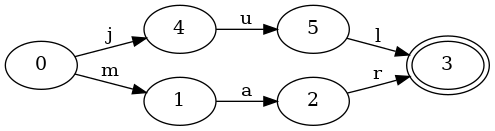

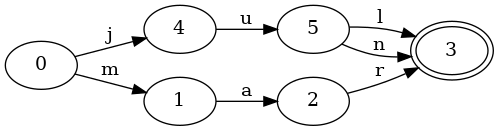

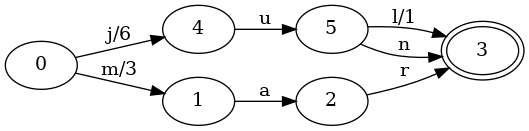

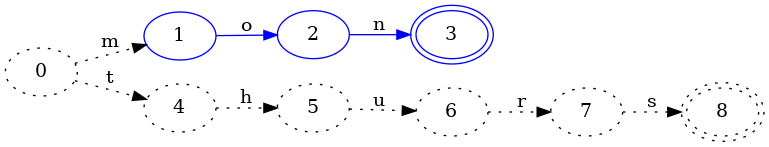

Let’s add another key to the set to see what it looks like. The following FSA represents an ordered set with keys “jul” and “mar”:

The FSA has grown a little more complex. The start state 0 now has two

transitions: j and m. Therefore, given the key mar, it will first

follow the m transition.

There’s one other important thing to notice here: the state 3 is shared

between the jul and mar keys. Namely, the state 3 has two transitions

entering it: l and r. This sharing of states between keys is really

important, because it enables us to store more information in a smaller space.

Let’s see what happens when we add jun to our set, which shares a common

prefix with jul:

Do you see the difference? It’s a small change. This FSA looks very much like

the previous one. There’s only one difference: a new transition, n, from

states 5 to 3 has been added. Notably, the FSA has no new states! Since

both jun and jul share the prefix ju, those states can be reused for both

keys.

Let’s switch things up a little bit and look at a set with the following keys:

october, november and december:

Since all three keys share the suffix ber in common, it is only encoded into

the FSA exactly once. Two of the keys share an even bigger suffix: ember,

which is also encoded into the FSA exactly once.

Before moving on to ordered maps, we should take a moment and convince ourselves that this is indeed an ordered set. Namely, given an FSA, how can we iterate over the keys in the set?

To demonstrate this, let’s use a set we built earlier with the keys jul,

jun and mar:

We can enumerate all keys in the set by walking the entire FSA by following transitions in lexicographic order. For example:

- Initialize at state

0.keyis empty. - Move to state

4. Addjtokey. - Move to state

5. Addutokey. - Move to state

3. Addltokey. Emitjul. - Move back to state

5. Droplfromkey. - Move to state

3. Addntokey. Emitjun. - Move back to state

5. Dropnfromkey. - Move back to state

4. Dropufromkey. - Move back to state

0. Dropjfromkey. - Move to state

1. Addmtokey. - Move to state

2. Addatokey. - Move to state

3. Addrtokey. Emitmar.

This algorithm is straight-forward to implement with a stack of the states to

visit and a stack of transitions that have been followed. It has time

complexity O(n) in the number of keys in the set with space complexity O(k)

where k is the size of the largest key in the set.

Ordered maps

As with ordered sets, an ordered map is like a map, but with an ordering defined on the keys of the map. Just like sets, ordered maps are typically implemented with a binary search tree or a btree, and unordered maps are typically implemented with a hash table. In our case, we will look at an implementation that uses a deterministic acyclic finite state transducer (abbreviated FST).

A deterministic acyclic finite state transducer is a finite state machine that is (the first two criteria are the same as the previous section):

- Deterministic. This means that at any given state, there is at most one transition that can be traversed for any input.

- Acyclic. This means that it is impossible to visit a state that has already been visited.

- A transducer. This means that the finite state machine emits a value associated with the specific sequence of inputs given to the machine. A value is emitted if and only if the sequence of inputs causes the machine to end in a final state.

In other words, an FST is just like an FSA, but instead of answering “yes”/“no” given a key, it will answer either “no” or “yes, and here’s the value associated with that key.”

In the previous section, representing a set only required one to store the keys in the transitions of the machine. The machine “accepts” an input sequence if and only if it represents a key in the set. In this case, a map needs to do more than just “accept” an input sequence; it also needs to return a value associated with that key.

One way to associate a value with a key is to attach some data to each transition. Just as an input sequence is consumed to move the machine from state to state, an output sequence can be produced as the machine moves from state to state. This additional “power” makes the machine a transducer.

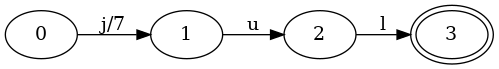

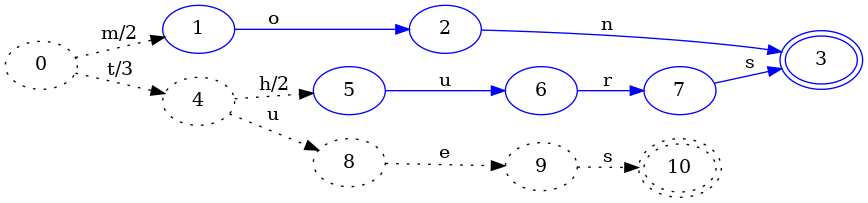

Let’s take a look at an example of a map with one element, jul, which is

associated with the value 7:

This machine is the same as the corresponding set, except that the first

transition j from state 0 to 1 has the output 7 associated with it.

The other transitions, u and l, also have an output 0 associated with

them that isn’t shown in the image.

As with sets, we can ask the map if it contains the key “jul.” But we also need to return the output. Here’s how the machine processes a key lookup for “jul”:

- Initialize

valueto0. - Given

j, the FST moves from the start state0to1. Add7tovalue. - Given

u, the FST moves from1to2. Add0tovalue. - Given

l, the FST moves from2to3. Add0tovalue.

Since all inputs have been fed to the FST, we can now ask: is the FST in a

final state? It is, so we know jul is in the map. Additionally, we can report

value as the value associated with the key jul, which is 7.

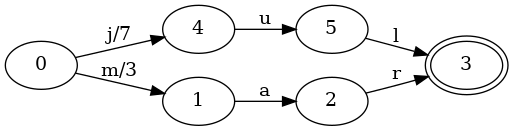

Not so amazing, right? The example is a bit too simplistic. A map with a single

key isn’t very instructive. Let’s see what happens when we add mar to the

map, associated with the value 3:

The start state has grown a new transition, m, with an output of 3. If we

lookup the key jul, then the process is the same as in the previous map:

we’ll get back a value of 7. If we lookup the key mar, then the process

looks like this:

- Initialize

valueto0. - Given

m, the FST moves from the start state0to1. Add3tovalue. - Given

a, the FST moves from1to2. Add0tovalue. - Given

r, the FST moves from2to3. Add0tovalue.

The only change here—other than following different input transitions—is

that 3 was added to value in the first move. Since all subsequent moves add

0 to value, the machine reports 3 as the value associated with mar.

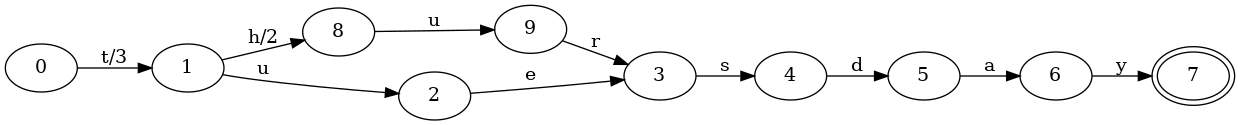

Let’s keep going. What happens when we have keys that share a common prefix?

Consider the same map as above, but with the jun key added associated with

the value 6:

As with sets, an additional n transition was added connecting states 5 and

3. But there were two additional changes!

- The

0->4transition for inputjhad its output changed from7to6. - The

5->3transition for inputlhad its output changed from0to1.

Those changes in outputs are really important, because it now changes some of

the details for looking up the value associated with the key jul:

- Initialize

valueto0. - Given

j, the FST moves from the start state0to4. Add6tovalue. - Given

u, the FST moves from4to5. Add0tovalue. - Given

l, the FST moves from5to3. Add1tovalue.

The final value is still 7, but we arrived at the value differently. Instead

of adding 7 in the initial j transition, we only added 6, but we made up

the extra 1 by adding it in the final l transition.

We should also convince ourselves that looking up the jun key is correct too:

- Initialize

valueto0. - Given

j, the FST moves from the start state0to4. Add6tovalue. - Given

u, the FST moves from4to5. Add0tovalue. - Given

n, the FST moves from5to3. Add0tovalue.

The first transition adds 6 to value, but we never add anything more than

0 to value on any subsequent transitions. This is because the jun key

does not go through the same final l transition that jul does. In this way,

both keys have distinct values, but we’ve done it in a way that shares much of

the data structure between keys with common prefixes.

Indeed, the key property that enables this sharing is that each key in the map corresponds to a unique path through the machine. Therefore, there will always be some combination of transitions followed for each key that is unique to that particular key. All we have to do is figure out how to place the outputs along the transitions. (We will see how to do this in the next section.)

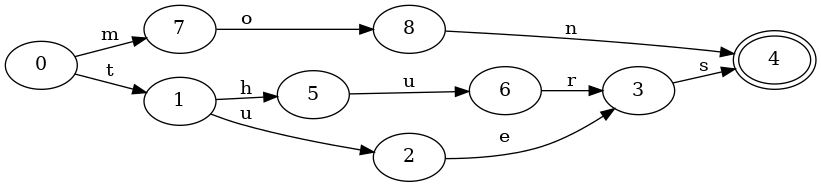

This sharing of outputs works for keys with both common prefixes and suffixes

too. Consider the keys tuesday and thursday, associated with the values 3

and 5, respectively (for day of the week).

Both keys have a common prefix, t, and a common suffix, sday. Notice that

the values associated with the keys also have a common prefix with respect to

addition on the values. Namely, 3 can be written as 3 + 0 and 5 can be

written as 3 + 2. This idea is captured in the machine; the common prefix t

has an output of 3, while the h transition (which is not present in

tuesday) has the output 2 associated with it. Namely, when looking up the

key tuesday, the first output on t will be emitted, but the h transition

won’t be followed, so the 2 output associated with it won’t be emitted. The

rest of the transitions have an output of 0, which does not change the final

value emitted.

The way I’ve described outputs might seem a bit restrictive; what if they aren’t integers? Indeed, the types of outputs that can be used in an FST are limited to things with the following operations defined:

- Addition.

- Subtraction.

- Prefix (i.e., find the prefix of two outputs).

Outputs must also have an additive identity, I, such that the following laws

hold:

x + I = xx - I = xprefix(x, y) = Iwhenxandydo not share a common prefix.

Integers satisfy this algebra trivially (where prefix is defined as min)

with the added benefit that they are very small. Other types can be made to

satisfy this algebra, but for now, we will only work with integers.

We only needed to use addition in the above examples, but we will need the other two operations for building a FST. That’s what we’ll cover next.

Construction

In the previous two sections, I have been careful to avoid talking about the construction of finite state machines that are used to represent ordered sets or maps. Namely, construction is a bit more complex than simple traversal.

To keep things simple, we place a restriction on the elements in our set or map: they must be added in lexicographic order. This is an onerous restriction, but we will see later how to mitigate it.

To motivate construction of finite state machines, let’s talk about tries.

Trie construction

A trie can be thought of as a deterministic acyclic finite state acceptor. Therefore, everything you learned in the previous section on ordered sets applies equally well to them. The only difference between a trie and the FSAs shown in this article is that a trie permits the sharing of prefixes between keys while an FSA permits the sharing of both prefixes and suffixes.

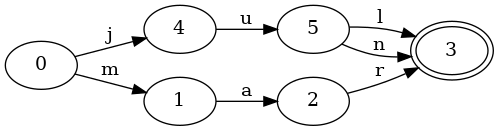

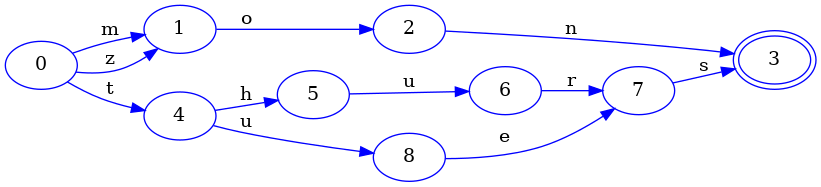

Consider a set with the keys mon, tues and thurs. Here is the

corresponding FSA that benefits from sharing both prefixes and suffixes:

And here is the corresponding trie, which only shares prefixes:

Notice that there are now three distinct final states, and the keys tues and

thurs require duplicating the final transition for s to the final state.

Constructing a trie is reasonably straight-forward. Given a new key to insert, all one needs to do is perform a normal lookup. If the input is exhausted, then the current state should be marked as final. If the machine stops before the input is exhausted because there are no valid transitions to follow, then simply create a new transition and node for each remaining input. The last node created should be marked final.

FSA construction

Recall that the only difference between a trie and an FSA is that an FSA permits the sharing of suffixes between keys. Since a trie is itself an FSA, we could construct a trie and then apply a general minimization algorithm, which would achieve our goal of sharing suffixes.

However, general minimization algorithms can be expensive both in time and space. For example, a trie can often be much larger than an FSA that shares structure between suffixes of keys. Instead, if we can assume that keys are added in lexicographic order, we can do better. The essential trick is realizing that when inserting a new key, any parts of the FSA that don’t share a prefix with the new key can be frozen. Namely, no new key added to the FSA can possibly make that part of the FSA smaller.

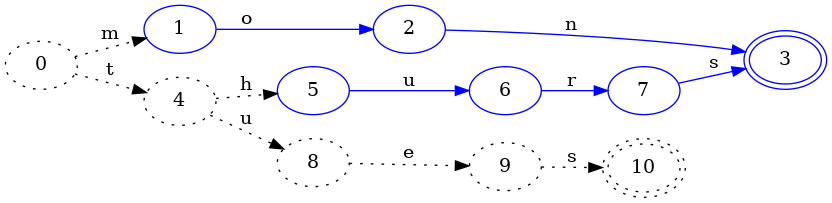

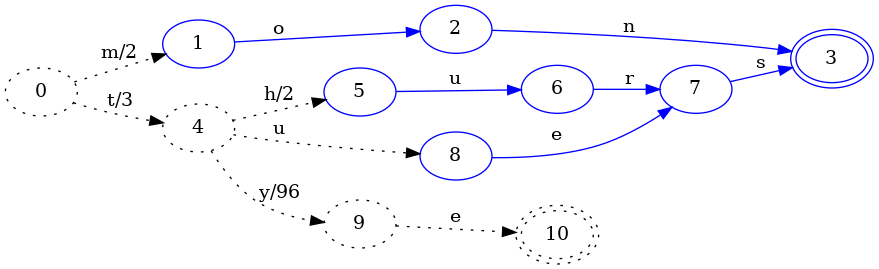

Some pictures might help explain this better. Consider again the keys mon,

tues and thurs. Since we must add them in lexicographic order, we’ll add

mon first, then thurs and then tues. Here’s what the FSA looks like after

the first key has been added:

This isn’t so interesting. Here’s what happens when we insert thurs:

The insertion of thurs caused the first key, mon, to be frozen (indicated

by blue coloring in the image). When a particular part of the FSA has been

frozen, then we know that it will never need to be modified in the future.

Namely, since all future keys added will be >= thurs, we know that no future

keys will start with mon. This is important because it lets us reuse that

part of the automaton without worrying about whether it might change in the

future. Stated differently, states that are colored blue are candidates for

reuse by other keys.

The dotted lines represent that thurs hasn’t actually been added to the FSA

yet. Indeed, adding it requires checking whether there exists any reusable

states. Unfortunately, we can’t do that yet. For example, it is true that

states 3 and 8 are equivalent: both are final and neither has any

transitions. However, it is not true that state 8 will always be equal to

state 3. Namely, the next key we add could, for example, be thursday. That

would change state 8 to having a d transition, which would make it not

equal to state 3. Therefore, we can’t quite conclude what the key thurs

looks like in the automaton yet.

Let’s move on to inserting the next key, tues:

In the process of adding tues, we deduced that the hurs part of the thurs

key could be frozen. Why? Because no future key inserted could possibly

minimize the path taken by hurs since keys are inserted in lexicographic

order. For example, we now know that the key thursday cannot ever be part of

the set, so we can conclude that the final state of thurs is equivalent to

the final state of mon: they are both final and both have no transitions, and

this will forever be true.

Notice that state 4 remained dotted: it is possible that state 4 could

change upon subsequent key insertions, so we cannot consider it equal to any

other state just yet.

Let’s add one more key to drive the point home. Consider the insertion of

zon:

We see here that state 4 has finally been frozen because no future

insertion after zon can possibly change the state 4. Additionally, we could

also conclude that thurs and tues share a common suffix, and that, indeed,

states 7 and 9 (from the previous image) are equivalent because neither of

them are final and both have a single transition with input s that points to

the same state. It is critical that both of their s transitions point to the

same state, otherwise we cannot reuse the same structure.

Finally, we must signal that we are done inserting keys. We can now freeze the

last portion of the FSA, zon, and look for redundant structure:

And of course, since mon and zon share a common suffix, there is indeed

redundant structure. Namely, the state 9 in the previous image is equivalent

in every way to state 1. This is only true because states 10 and 11 are

also equivalent to states 2 and 3. If that weren’t true, then we couldn’t

consider states 9 and 1 equal. For example, if we had inserted the key

mom into our set and still assumed that states 9 and 1 were equal, then

the resulting FSA would look something like this:

And this would be wrong! Why? Because this FSA will claim that the key zom is

in the set—but we never actually added it.

Finally, it is worth noting that the construction algorithm outlined here can

run in O(n) time where n is the number of keys. It is easy to see that

inserting a key initially into the FST without checking for redundant structure

does not take any longer than looping over each character in the key, assuming

that looking up a transition in each state takes constant time. The trickier

bit is: how do we find redundant structure in constant time? The short answer

is a hash table, but I will explain some of the challenges with that in the

section on construction in practice.

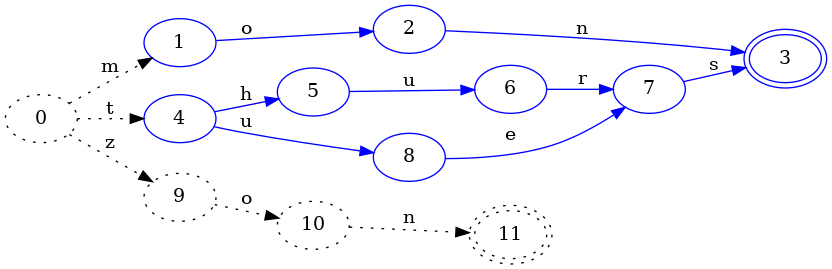

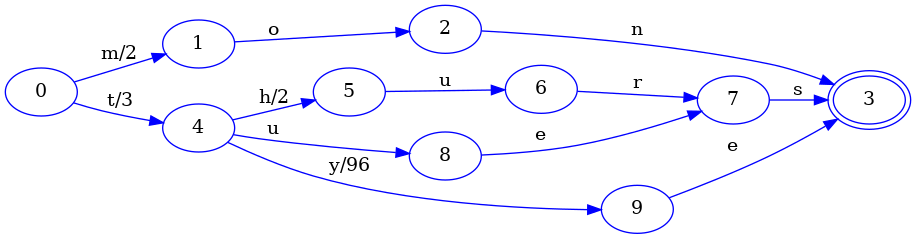

FST construction

Constructing deterministic acyclic finite state transducers works in much the same way as constructing deterministic acyclic finite state acceptors. The key difference is the placement and sharing of outputs on transitions.

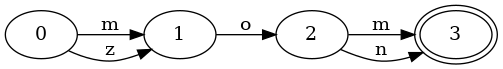

To keep the mental burden low, we will reuse the example in the previous

section with keys mon, tues and thurs. Since FSTs represent maps, we will

associate the numeric day of the week with each key: 2, 3 and 5,

respectively.

As before, we’ll start with inserting the first key, mon:

(Recall that the dotted lines correspond to pieces of the FST that may change on subsequent key insertion.)

This isn’t so interesting, but it is at least worth noting that the output 2

is placed on the first transition. Technically, the following transducer would

be equally correct:

However, placing the outputs as close to the initial state as possible makes it much easier to write an algorithm that shares output transitions between keys.

Let’s move on to inserting the key thurs mapped to the value 5:

As with FSA construction, insertion of the key thurs allows us to conclude

that the mon portion of the FST will never change. (As represented in the

image by the color blue.)

Since the mon and thurs keys don’t share a common prefix and they are the

only two keys in the map, their entire output values can each be placed in the

first transition out of the start state.

However, when we add the next key, tues, things get a little more

interesting:

As with FSA construction, this identifies another portion of the FST that can

never change and freezes it. The difference here is that the output on the

transition from state 0 to 4 has changed from 5 to 3. This is because

the tues key’s value is 3, so if the initial t transition added 5 to

the value, then the value would be too big. We want to share as much structure

as is possible, so when we identify a common prefix, we look for the common

prefix in the output values as well. In this case, the prefix of 5 and 3 is

3. Since 3 is the value associated with the key tues, its remaining

transitions can all have an output of 0.

However, if we changed the output of the 0->4 transition from 5 to 3, the

value associated with the key thurs would now be wrong. We then have to

“push” the left over value from taking the prefix of 5 and 3 down. In this

case 5 - 3 = 2, so we add 2 to each transition on 4 (except for the new

u transition we added).

In this way, we preserve the outputs of previous keys, add a new output for a new key and share as much structure as possible in the FST.

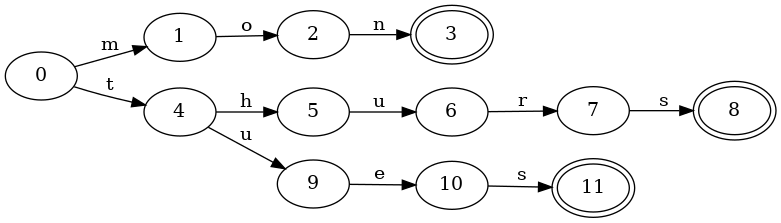

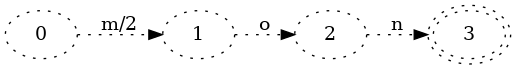

As with before, let’s try adding one more key. This time, let’s pick a key that

has a more interesting impact on outputs. Let’s add tye to the map and

associate it with the value 99 to see what happens.

Insertion of the tye key allowed us to freeze the es part of the tues

key. In particular, as with FSA construction, we identified equivalent states

so that thurs and tues could share states in the FST.

What is different here for FST construction is that the output associated with

the 4->9 transition (which was just added for the tye key) has an output of

96. It chose 96 because the transition prior to it, 0->4, has an output

of 3. Since the common prefix of 99 and 3 is 3, the output of 0->4 is

left unchanged, and the output for 4->9 is set to 99 - 3 = 96.

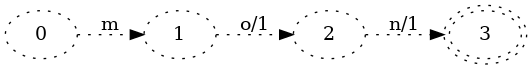

For completeness, here is the final FST after indicating that no more keys will be added:

The only real change here from the previous step is that the final transition

of the tye key is connected to the final state shared by all other keys.

Construction in practice

Actually writing the code to implement the pictorially described algorithms

above is a bit beyond the scope of this article. (A fast implementation of it

is of course freely available in my fst

library.) However, there are some important challenges worth discussing.

One of the critical use cases of an FST data structure is its ability to store and search a very large number of keys. This goal is somewhat at odds with the algorithm described above, since it requires one to keep all frozen states in memory. Namely, in order to detect whether there are parts of the FST that can be reused for a given key, you must be able to actually search for equivalent states.

The literature which describes this algorithm (linked in the next section) states that one can use a hash table for this, which provides constant time access to any particular state (assuming a good hash function). The problem with this approach is that a hash table usually incurs some kind of overhead, in addition to actually storing all of the states in memory.

It is possible to mitigate the onerous memory required by sacrificing

guaranteed minimality of the resulting FST. Namely, one can maintain a hash

table that is bounded in size. This means that commonly reused states are

kept in the hash table while less commonly reused states are evicted. In

practice, a hash table with about 10,000 slots achieves a decent compromise

and closely approximates minimality in my own unscientific experiments. (The

actual implementation does a little better and stores a small LRU cache in each

slot, so that if two common but distinct nodes map to the same bucket, they can

still be reused.)

An interesting consequence of using a bounded hash table which only stores some of the states is that construction of an FST can be streamed to a file on disk. Namely, when states are frozen as described in the previous two sections, there’s no reason to keep all of them in memory. Instead, we can immediately write them to disk (or a socket, or whatever).

The end result is that we can construct an approximately minimal FST from pre-sorted keys in linear time and in constant memory.

References

The algorithms presented above are not my own. (I did, to the best of my knowledge, come up with the LRU cache idea. But that’s it!)

I got the algorithm for FSA construction from Incremental Construction of Minimal Acyclic Finite State Automata. In particular, section 3 does a reasonably good job of explaining the particulars, but the paper overall is a good read.

I got the algorithm for FST construction from Direct Construction of Minimal Acyclic Subsequential Transducers. The whole paper is a really good read, but I had to read it about 3-5 times over the course of a week to really let it sink in. There is pseudo-code for the algorithm near the end of the paper, which is very readable once your brain gets acclimated to what all of the variables mean.

Those two papers pretty much cover everything in the article so far. However, there is more worth reading to actually write an efficient implementation. In particular, this article will not cover in detail how nodes and transitions are represented in an FST. The short answer is that the representation of an FST is a sequence of bytes in memory and the vast majority of states take up exactly one byte of space. Indeed, representing finite state machines is an active area of research. Here are two papers that helped me the most:

- Experiments with Automata Compression (Unfortunately, if you click on this link, researchgate.net will seem to redirect you to a very unfriendly UI. If you just want the PDF already, copy the link and paste it directly in your address bar. The actual article is on page 116 of the PDF or page 105 of the conference collection.)

- Smaller Representation of Finite State Automata

For an excellent but very long and in depth overview of the field, Jan Daciuk’s dissertation (gzipped PostScript warning) is excellent.

For a short and sweet experimentally motivated overview of construction algorithms, Comparison of Construction Algorithms for Minimal, Acyclic, Deterministic, Finite-State Automata from Sets of Strings is very good.

The FST library

The fst crate (Rust’s word for “compilation unit”) I built is written in

Rust, fast and memory conscious. It provides two convenient abstractions

around ordered sets and ordered maps, while also providing raw access to the

underlying finite state transducer. Loading sets and maps using memory maps is

a first class feature, which makes it possible to query sets or maps without

loading the entire data structure into memory first.

The capabilities of ordered sets and maps mirror that of

BTreeSet

and

BTreeMap

found in Rust’s standard library.

The key difference is that sets and maps in fst are immutable, keys are fixed

to byte sequences, and values, in the case of maps, are always unsigned 64 bit

integers.

In this section, we will tour the following topics:

- Building ordered sets and maps represented by finite state machines.

- Querying ordered sets and maps.

- Executing general automatons against a set or a map. We’ll cover Levenshtein automatons (for fuzzy searching) and regular expressions as two interesting examples.

- Performing efficient streaming set operations (e.g., intersection and union) on many sets or maps at once.

- A brief look at querying the transducer directly as a finite state machine.

As such, this section will be very heavy on Rust code. I’ll do my best to attach high level descriptions of what’s going on in the code so that you don’t need to know Rust in order to know what’s happening. With that said, to get the most out of this section, I’d recommend reading the excellent Rust Programming Language book.

Additionally, you may also find it useful to keep the

fst API documentation

handy, which may act as a nice supplement to the material in this section.

Building ordered sets and maps

Most data structures in Rust are mutable, which means queries, insertions and deletions are all bundled up neatly in a single API. Data structures built on the FSTs described in this blog post are unfortunately a different animal, because once they are built, they can no longer be modified. Therefore, there is a division in the API the distinguishes between building an FST and querying an FST.

This division is reflected in the types exposed by the fst library. Among

them are Set and SetBuilder, where the former is for querying and the

latter is for insertion. Maps have a similar dichotomy with Map and

MapBuilder.

Let’s get on to a simple example that builds a set and writes it to a file. A really important property of this code is that the set is written to the file as it is being constructed. At no time is the entire set actually stored in memory!

(If you’re not familiar with Rust, I’ve attempted to be a bit verbose in the comments.)

// Imports the `File` type into this scope and the entire `std::io` module.

use std::fs::File;

use std::io;

// Imports the `SetBuilder` type from the `fst` module.

use fst::SetBuilder;

// Create a file handle that will write to "set.fst" in the current directory.

let file_handle = File::create("set.fst")?;

// Make sure writes to the file are buffered.

let buffered_writer = io::BufWriter::new(file_handle);

// Create a set builder that streams the data structure to set.fst.

// We could use a socket here, or an in memory buffer, or anything that

// is "writable" in Rust.

let mut set_builder = SetBuilder::new(buffered_writer)?;

// Insert a few keys from the greatest band of all time.

// An insert can fail in one of two ways: either a key was inserted out of

// order or there was a problem writing to the underlying file.

set_builder.insert("bruce")?;

set_builder.insert("clarence")?;

set_builder.insert("stevie")?;

// Finish building the set and make sure the entire data structure is flushed

// to disk. After this is called, no more inserts are allowed. (And indeed,

// are prevented by Rust's type/ownership system!)

set_builder.finish()?;(If you aren’t familiar with Rust, you’re probably wondering: what the heck is

that ? thing? Well, in short, it’s an operator that uses early returns and

polymorphism to handle errors for us. The best way to think of it is: every

time you see ?, it means the underlying operation may fail, and if it

does, return the error value and stop executing the current function. See my

other blog post on error handling in Rust for more

details.

At a high level, this code is:

- Creating a file and wrapping it in a buffer for fast writing.

- Create a

SetBuilderthat writes to the file we just created. - Inserts keys into the set using the

SetBuilder::insertmethod. - Closes the set and flushes the data structure to disk.

Sometimes though, we don’t need or want to stream the set to a file on disk. Sometimes we just want to build it in memory and use it. That’s possible too!

use fst::{Set, SetBuilder};

// Create a set builder that streams the data structure to memory.

let mut set_builder = SetBuilder::memory();

// Inserts are the same as before.

// They can still fail if they are inserted out of order, but writes to the

// heap are (mostly) guaranteed to succeed. Since we know we're inserting these

// keys in the right order, we use "unwrap," which will panic or abort the

// current thread of execution if it fails.

set_builder.insert("bruce").unwrap();

set_builder.insert("clarence").unwrap();

set_builder.insert("stevie").unwrap();

// Finish building the set and get back a region of memory that can be

// read as an FST.

let fst_bytes = set_builder.into_inner()?;

// And create a new Set with those bytes.

// We'll cover this more in the next section on querying.

let set = Set::from_bytes(fst_bytes).unwrap();This code is mostly the same as before with two key differences:

- We no longer need to create a file. We just instruct the

SetBuilderto allocate a region of memory and use that instead. - Instead of calling

finishat the end, we callinto_innerinstead. This does the same thing as callingfinish, but it also gives us back the region of memory thatSetBuilderused to write the data structure to. We then create a newSetfrom this region of memory, which could then be used for querying.

Let’s now take a look at the same process, but for maps. It is almost exactly the same, except we now insert values with keys:

use fst::{Map, MapBuilder};

// Create a map builder that streams the data structure to memory.

let mut map_builder = MapBuilder::memory();

// Inserts are the same as before, except we include a value with each key.

map_builder.insert("bruce", 1972).unwrap();

map_builder.insert("clarence", 1972).unwrap();

map_builder.insert("stevie", 1975).unwrap();

// These steps are exactly the same as before.

let fst_bytes = map_builder.into_inner()?;

let map = Map::from_bytes(fst_bytes).unwrap();This is pretty much all there is to building ordered sets or maps represented by FSTs. There is API documentation for both sets and maps.

A builder shortcut

In the examples above, we had to create a builder, insert keys one by one and

then finally call finish or into_inner before we could declare the process

of building a set or a map done. This is often convenient in practice (for

example, iterating over lines in a file), but it is not so convenient for

presenting concise examples in a blog post. Therefore, we will use a small

convenience.

The following code builds a set in memory:

use fst::Set;

let set = Set::from_iter(vec!["bruce", "clarence", "stevie"])?;This will achieve the same result as before. The only difference is that we are allocating a dynamically growable vector of elements before constructing the set, which is typically not advisable on large data.

The same trick works for maps, which takes a sequence of tuples (keys and values) instead of a sequence of byte strings (keys):

use fst::Map;

let map = Map::from_iter(vec![

("bruce", 1972),

("clarence", 1972),

("stevie", 1975),

])?;Querying ordered sets and maps

Building an FST based data structure isn’t exactly a model of convenience. In particular, many of the operations can fail, especially when writing the data structure directly to a file. Therefore, construction of an FST based data structure needs to do error handling.

Thankfully, this is not the case for querying. Once a set or a map has been constructed, we can query it with reckless abandon.

Sets are simple. The key operation is: “does the set contain this key?”

use fst::Set;

let set = Set::from_iter(vec!["bruce", "clarence", "stevie"])?;

assert!(set.contains("bruce")); // "bruce" is in the set

assert!(!set.contains("andrew")); // "andrew" is not

// Another obvious operation: how many elements are in the set?

assert_eq!(set.len(), 3);Maps are once again very similar, but we can also access the value associated with the key.

use fst::Map;

let map = Map::from_iter(vec![

("bruce", 1972),

("clarence", 1972),

("stevie", 1975),

])?;

// Maps have `contains_key`, which is just like a set's `contains`:

assert!(map.contains_key("bruce")); // "bruce" is in the map

assert!(!map.contains_key("andrew")); // "andrew" is not

// Maps also have `get`, which retrieves the value if it exists.

// `get` returns an `Option<u64>`, which is something that can either be

// empty (when the key does not exist) or present with the value.

assert_eq!(map.get("bruce"), Some(1972)); // bruce joined the band in 1972

assert_eq!(map.get("andrew"), None); // andrew was never in the band

In addition to simple membership testing and key lookup, sets and maps also provide iteration over their elements. These are ordered sets and maps, so iteration yields elements in lexicographic order of the keys.

use std::str::from_utf8; // converts UTF-8 bytes to a Rust string

// We import the usual `Set`, but also include `Streamer`, which is a trait

// that makes it possible to call `next` on a stream.

use fst::{Streamer, Set};

// Store the keys somewhere so that we can compare what we get with them and

// make sure they're the same.

let keys = vec!["bruce", "clarence", "danny", "garry", "max", "roy", "stevie"];

// Pass a reference with `&keys`. If we had just used `keys` instead, then it

// would have *moved* into `Set::from_iter`, which would prevent us from using

// it below to check that the keys we got are the same as the keys we gave.

let set = Set::from_iter(&keys)?;

// Ask the set for a stream of all of its keys.

let mut stream = set.stream();

// Iterate over the elements and collect them.

let mut got_keys = vec![];

while let Some(key) = stream.next() {

// Keys are byte sequences, but the keys we inserted are strings.

// Strings in Rust are UTF-8 encoded, so we need to decode here.

let key = from_utf8(key)?.to_string();

got_keys.push(key);

}

assert_eq!(keys, got_keys);(If you’re a Rustacean and you’re wondering why in the heck we’re using while let here instead of a for loop or an iterator adapter, then it is time to

let you in on a dirty little secret: the fst crate doesn’t expose iterators.

Instead, it exposes streams. The technical justification is explained at

length on the documentation for the Streamer

trait.)

In this example, we’re asking the set for a stream, which lets us iterate over

all of the keys in the set in order. The stream yields a reference to an

internal buffer maintained by the stream. In Rust, this is a totally safe thing

to do, because the type system will prevent you from calling next on a stream

if a reference to its internal buffer is still alive (at compile time). This

means that you as the consumer get to control whether all of the keys are

stored in memory (as in this example), or if your task only requires a single

pass over the data, then you never need to allocate space for each key. This

style of iteration is called streaming because ownership of the elements is

tied to the iteration itself.

It is important to note that this process is distinctly different from other

data structures such as BTreeSet. Namely, a tree based data structure

usually has a separate location allocated for each key, so it can simply

return a reference to that allocation. That is, ownership of elements yielded

by iteration is tied to the data structure. We can’t achieve this style of

iteration with FST based data structures without an unacceptable cost for each

iteration. Namely, an FST does not store each key in its own location. Recall

from the first part of this article that keys are stored in the transitions

of the finite state machine. Therefore, the keys are constructed during the

process of iteration.

OK, back to querying. In addition to iterating over all the keys, we can also iterate over a subset of the keys efficiently with range queries. Here’s an example that builds on the previous one.

// We now need the IntoStreamer trait, which provides a way to convert a

// range query into a stream.

use fst::{IntoStreamer, Streamer, Set};

// Same as previous example.

let keys = vec!["bruce", "clarence", "danny", "garry", "max", "roy", "stevie"];

let set = Set::from_iter(&keys)?;

// Build a range query that includes all keys greater than or equal to `c`

// and less than or equal to `roy`.

let range = set.range().ge("c").le("roy");

// Turn the range into a stream.

let stream = range.into_stream();

// Use a convenience method defined on streams to collect the elements in the

// stream into a sequence of strings. This is effectively a shorter form of the

// `while let` loop we wrote out in the previous example.

let got_keys = stream.into_strs()?;

// Check that we got the right keys.

assert_eq!(got_keys, &keys[1..6]);The key line in the above example was this:

let range = set.range().ge("c").le("roy");The method range returns a new range query, and the ge and le methods set

the greater-than-or-equal and less-than-or-equal to bounds, respectively. There

are also gt and lt methods, which set greater-than and less-than bounds,

respectively. Any combination of these methods can be used (if one is used more

than once, the last one overwrites the previous one).

Once the range query is built, it can be turned into a stream easily:

let stream = range.into_stream();Once we have a stream, we can iterate over it using the next method and a

while let loop, as we saw in a previous example. In this example, we instead

called the into_strs method, which does the iteration and UTF-8 decoding for

you, returning the results in a vector.

The same methods are available on maps as well, except the iteration yields tuples of keys and values instead of just the key.

Memory maps

Remember the first example for SetBuilder where we streamed the data

structure straight to a file? It turns out that this is a really important use

case for FST based data structures specifically because their wheelhouse is

huge collections of keys. Being able to write the data structure as it’s

constructed straight to disk without storing the entire data structure in

memory is a really nice convenience.

Can we do something similar for reading a set from disk? Certainly, opening the

file, reading its contents and using that to create a Set is possible:

use std::fs::File;

use std::io::Read;

use fst::Set;

// Open a handle to a file and read its entire contents into memory.

let mut file_handle = File::open("set.fst")?;

let mut bytes = vec![];

file_handle.read_to_end(&mut bytes)?;

// Construct the set.

let set = Set::from_bytes(bytes)?;

// Finally, we can query.

println!("number of elements: {}", set.len());The expensive part of this code is having to read the entire file into memory.

The call to Set::from_bytes is actually quite fast. It reads a little bit of

meta data encoded into the FST and does a simplistic checksum. In fact, this

process only requires looking at 32 bytes!

One possible way to mitigate this is to teach the FST data structure how to

read directly from a file. In particular, it would know to issue seek system

calls to jump around in the file to traverse the finite state machine.

Unfortunately, this can be prohibitively expensive because calling seek would

happen very frequently. Every seek entails the overhead of a system call,

which would likely make searching the FST prohibitively slow.

Another way to mitigate this is to maintain a cache that is bounded in size and stores chunks of the file in memory, but probably not all of it. When a region of the file needs to be accessed that’s not in the cache, a chunk of the file that includes that region is read and added to the cache (possibly evicting a chunk that hasn’t been accessed in a while). When we access that region again and it is already in the cache, then no I/O is required. This approach also enables us to be smart about what is stored in memory. Namely, we could make sure all chunks near the initial state of the machine are in the cache, since those would in theory be the most frequently accessed. Unfortunately, this approach is complex to implement and has other problems.

A third way is something called a

memory mapped file.

When a memory mapped file is created, it is exposed to us as if it were a

sequence of bytes in memory. When we access this region of memory, it’s

possible that there is no actual data there from the file to be read yet. This

causes a page fault which tells the operating system to read a chunk from the

file and make it available for use in the sequence of bytes exposed to the

program. The operating system is then in charge of which pieces of the file are

actually in memory. The actual process of reading data from the file and

storing it in memory is transparent to our program—all the fst crate sees

is a normal sequence of bytes.

This third way is actually very similar to our idea above with a cache. The key

difference is that the operating system manages the cache instead of us. This

is a dramatic simplification in the implementation. Of course, there are some

costs. Since the operating system manages the cache, it can’t know that certain

parts of the FST should always stay in memory. Therefore, on occasion, we may

not have optimal query times. These downsides can be mitigated somewhat through

the use of calls like mlock or madvise, which permits your process to tell

the operating system that certain regions of the memory map should stay in or

out of memory.

The fst crate supports using memory maps (but does not yet use mlock or

madvise). Here is our previous example, but modified to use a memory map:

use fst::Set;

// Construct the set from a file path. The fst crate implements this using a

// memory map, which is why this method is unsafe to call. Callers must ensure

// that they do not open another mutable memory map in the same program.

let set = unsafe { Set::from_path("set.fst")? };

// Finally, we can query. This can happen immediately, without having

// to read the entire set into memory.

println!("number of elements: {}", set.len());That’s all there is to it. Querying remains the same. The fact that a memory map is being used is completely transparent to your program.

There is one more cost worth mentioning here. The format used to represent an FST in memory militates toward random access of the data. Namely, looking up a key may jump around to different regions of the FST that are not close to each other at all. This means that reading an FST from disk through a memory map can be costly because random access I/O is slow. This is particularly true when using a non-solid state disk since random access will require a lot of physical seeking. If you find yourself in this situation and the operating system’s page cache can’t compensate, then you may need to pay the upfront cost and load the entire FST into memory. Note that this isn’t quite a death sentence, since the purpose of an FST is to be very small. For example, an FST with millions of keys can fit in a few megabytes of memory. (e.g., All 3.5 million unique words from Project Gutenberg’s entire corpus occupies only 22 MB.)

Levenshtein automata

Given a collection of strings, one really useful operation is fuzzy searching. There are many different types of fuzzy searching, but we will only cover one here: fuzzy search by Levenshtein or “edit” distance.

Levenshtein distance is a way to compare two strings. Namely, given strings A

and B, the Levenshtein distance of A and B is the number of character

insertions, deletions and substitutions one must perform to transform A into

B. Here are some simple examples:

dist("foo", "foo") == 0(no change)dist("foo", "fo") == 1(one deletion)dist("foo", "foob") == 1(one insertion)dist("foo", "fob") == 1(one substitution)dist("foo", "fobc") == 2(one substitution, one insertion)

There are a

variety of ways

to implement an algorithm that computes the Levenshtein distance between two strings.

To a first approximation, the best one can do is O(mn) time, where m and

n are the lengths of the strings being compared.

For our purposes, the question we’d like to answer is: does this key match any

of the keys in the set up to an Levenshtein distance of n?

Certainly, we could implement an algorithm to compute Levenshtein distance

between two strings, iterate over the keys in one of our FST based ordered

sets, and run the algorithm for each key. If the distance between the query and

the key is <= n, then we emit it as a match. Otherwise, we skip the key and

move on to the next.

The problem with this approach is that it is incredibly slow. It requires running an effectively quadratic algorithm over every key in the set. Not good.

It turns out that for our specific use case, we can do a lot better than that. Namely, in our case, one of the strings in every distance computation for a single search is fixed; the query remains the same. Given these conditions, and a known distance threshold, we can build an automaton that recognizes all strings that match our query.

Why is that useful? Well, our FST based ordered set is an automaton! That means answering the question with our ordered set is no different than taking the intersection of two automatons. This is really fast.

Here is a quick example that demonstrates a fuzzy search on an ordered set.

// We've seen all these imports before except for Levenshtein.

// Levenshtein is a type that knows how to build Levenshtein automata.

use fst::{IntoStreamer, Streamer, Set};

use fst_levenshtein::Levenshtein;

let keys = vec!["fa", "fo", "fob", "focus", "foo", "food", "foul"];

let set = Set::from_iter(keys)?;

// Build our fuzzy query. This says to search for "foo" and return any keys

// that have a Levenshtein distance from "foo" of no more than 1.

let lev = Levenshtein::new("foo", 1)?;

// Apply our fuzzy query to the set we built and turn the query into a stream.

let stream = set.search(lev).into_stream();

// Get the results and confirm that they are what we expect.

let keys = stream.into_strs()?;

assert_eq!(keys, vec![

"fo", // 1 deletion

"fob", // 1 substitution

"foo", // 0 insertions/deletions/substitutions

"food", // 1 insertion

]);A really important property of using an automaton to search our set is that it

can efficiently rule out entire regions of our set to search. Namely, if our

query is food with a distance threshold of 1, then it won’t ever visit keys

in the underlying FST with a length greater than 5 precisely because such

keys will never meet our search criteria. It can also skip many other keys, for

example, any keys starting with two letters that are neither f nor o. Such

keys can also never match our search criteria because they already exceed the

distance threshold.

Unfortunately, talking about exactly how Levenshtein automata are implemented is beyond the scope of this article. The implementation is based in part on the insights from Jules Jacobs. However, there is a part of this implementation that is worth talking about: Unicode.

Levenshtein automata and Unicode

In the previous section, we saw an example of some code that builds a

Levenshtein automaton,

which can be used to fuzzily search an ordered set or map in the fst crate.

A really important detail that we glossed over is how the Levenshtein distance is actually defined. Here is what I said, emphasis added:

Levenshtein distance is a way to compare two strings. Namely, given strings

AandB, the Levenshtein distance ofAandBis the number of character insertions, deletions and substitutions one must perform to transformAintoB.

What exactly is a “character” and how do our FST based ordered sets and maps handle it? There is no one true canonical definition of what a character is, and therefore, it was a poor choice of words for technical minds. A better word, which reflects the actual implementation, is the number of Unicode codepoints. That is, the Levenshtein distance is the number of Unicode codepoint insertions, deletions or substitutions to transform one key into another.

Unfortunately, there isn’t enough space to go over Unicode here, but Introduction to Unicode is an informative read that succinctly defines important terminology. David C. Zentgraf’s write up is also good, but much longer and more detailed. The important points are as follows:

- A Unicode codepoint approximates something we humans think of as a character.

- This is not true in general, since multiple codepoints may build something that we humans think of as a single character. In Unicode, these combinations of codepoints are called grapheme clusters.

- A codepoint is a 32 bit number that can be encoded in a variety of ways. The encoding Rust biases toward is UTF-8, which represents every possible codepoint by 1, 2, 3 or 4 bytes.

Our choice to use codepoints is a natural trade off between correctness,

implementation complexity and performance. The simplest thing to implement is

to assume that every single character is represented by a single byte. But what

happens when a key contains ☃ (a Unicode snowman, which is a single

codepoint), which is encoded as 3 bytes in UTF-8? The user sees it as a single

character, but the Levenshtein automaton would see it as 3 characters.

That’s bad.

Since our FSTs are indeed byte based (i.e., every transition in the

transducer corresponds to exactly one byte), that implies that our

Levenshtein automaton must have UTF-8 decoding built into it. The

implementation I wrote is based on a trick employed by Russ Cox for

RE2 (who, in turn, got it from Ken

Thompson’s grep). You can read more about it in the documentation of the

utf8-ranges crate.

A really cool property that falls out of this approach is that if you execute a Levenshtein query using this crate, than all keys are guaranteed to be valid UTF-8. If a key isn’t valid UTF-8, then the Levenshtein automaton simply would not match it.

Regular expressions

Another type of query we might want to run on our FST based data structures is

a regular expression. Put simply, a regular expression is a simple pattern

syntax that describes regular languages. For example, the regular expression

[0-9]+(foo|bar) matches any text that starts with one or more numeric digits

followed by either foo or bar.

It sure would be nice to search our sets or maps using a regular expression. One way to do it would be to iterate over all of the keys and apply the regular expression to each key. If there’s no match, skip the key. Unfortunately, this will be quite slow. Rust’s regular expressions are no slouch, but executing a regular expression millions on times on small strings is bound to be slow. More importantly, using this approach, we must visit every key in the set. For a large set, this might make a regular expression query not feasible.

As with computing Levenshtein distance in the previous section, it turns out we can do a lot better than that. Namely, since our regular expression stays the same throughout our search, we can pre-compute an automaton that knows how to match any text against the regular expression. Since our sets and maps are themselves automatons, this means we can very efficiently search our data structures by intersecting the two automatons.

Here’s a simple example:

// We've seen all these imports before except for Regex.

// Regex is a type that knows how to build regular expression automata.

use fst::{IntoStreamer, Streamer, Set};

use fst_regex::Regex;

let keys = vec!["123", "food", "xyz123", "τροφή", "еда", "מזון", "☃☃☃"];

let set = Set::from_iter(keys)?;

// Build a regular expression. This can fail if the syntax is incorrect or

// if the automaton becomes too big.

// This particular regular expression matches keys that are not empty and

// only contain letters. Use of `\pL` here stands for "any Unicode codepoint

// that is considered a letter."

let lev = Regex::new(r"\pL+")?;

// Apply our regular expression query to the set we built and turn the query

// into a stream.

let stream = set.search(lev).into_stream();

// Get the results and confirm that they are what we expect.

let keys = stream.into_strs()?;

// Notice that "123", "xyz123" and "☃☃☃" did not match.

assert_eq!(keys, vec![

"food",

"τροφή",

"еда",

"מזון",

]);In this example, we show how to execute a regular expression query against an

ordered set. The regular expression is \pL+, which will only match non-empty

keys that correspond to a sequence of UTF-8 encoded codepoints that are

considered letters. Digits like 2 and cool symbols like ☃ (Unicode snowman)

aren’t considered letters, so the keys that contain those symbols don’t match

our regular expression.

Regular expression queries share two important similarities with Levenshtein queries:

- A regular expression can only match keys which are valid UTF-8. This means that all keys returned by a regular expression query are guaranteed to be valid UTF-8. The regular expression automaton guarantees this in the same way that the Levenshtein automaton guarantees it: it builds UTF-8 decoding into the automaton itself.

- A regular expression query will not necessarily visit all keys in the set.

Namely, keys like

123that don’t begin with a letter are ruled out immediately. A key likexyz123is ruled out as soon as1is seen.

As with Levenshtein automata, we unfortunately won’t talk about how the

automaton is implemented. In fact, this topic is quite big, and

Russ Cox’s series of articles on the topic

is authoritative. It’s also worth noting that thanks to the

regex-syntax

crate, it was actually feasible to do this. This way, we are guaranteed to

share the same exact syntax as Rust’s

regex

crate. (A regular expression parser is often one of the more difficult aspects

of the implementation!)

One final note: it is very easy to write a regular expression that will take a

long time to match on a large set. For example, if the regular expression

starts with .* (which means “match zero or more Unicode codepoints”), then it

will likely result in visiting every key in the automaton.

Set operations

There is one last thing we need to talk about to wrap up basic querying: set

operations. Some common set operations supported by the fst crate are union,

intersection, difference and symmetric difference. All of these operations can

work efficiently on any number of sets or maps.

This is particularly useful if you have multiple sets or maps on disk that

you’d like to search. Since the fst crate encourages memory mapping them, it

means we can search many sets nearly instantly.

Let’s take a look at an example that searches multiple FSTs and combines the search results into a single stream.

use std::str::from_utf8;

use fst::{Streamer, Set};

use fst::set;

// Create 5 sets. As a convenience, these are stored in memory, but they could

// just as easily have been memory mapped from disk using `Set::from_path`.

let set1 = Set::from_iter(&["AC/DC", "Aerosmith"])?;

let set2 = Set::from_iter(&["Bob Seger", "Bruce Springsteen"])?;

let set3 = Set::from_iter(&["George Thorogood", "Golden Earring"])?;

let set4 = Set::from_iter(&["Kansas"])?;

let set5 = Set::from_iter(&["Metallica"])?;

// Build a set operation. All we need to do is add a stream from each set and

// ask for the union. (Other operations, such as `intersection`, are also

// available.)

let mut stream =

set::OpBuilder::new()

.add(&set1)

.add(&set2)

.add(&set3)

.add(&set4)

.add(&set5)

.union();

// Now collect all of the keys. `stream` is just like any other stream that

// we've seen before.

let mut keys = vec![];

while let Some(key) = stream.next() {

let key = from_utf8(key)?.to_string();

keys.push(key);

}

assert_eq!(keys, vec![

"AC/DC", "Aerosmith", "Bob Seger", "Bruce Springsteen",

"George Thorogood", "Golden Earring", "Kansas", "Metallica",

]);This example builds 5 different sets in memory, creates a new set operation, adds a stream from each set to the build and then asks for the union of all of the streams.

The union set operation, like all the others, are implemented in a streaming

fashion. That is, none of the operations require storing all of the keys in

memory precisely because the keys in each set are ordered. (The actual

implementation uses a data structure called a binary

heap.)

The cool thing about streams is that they are composable. In particular, it would be very sad if you were only limited to taking the union of entire sets. Instead, you can actually issue any type of query on the sets and take the union.

Here’s the same example as above, but with a regular expression that only matches keys with at least one space in them:

use std::str::from_utf8;

use fst::{Streamer, Set};

use fst::set;

use fst_regex::Regex;

// Create 5 sets. As a convenience, these are stored in memory, but they could

// just as easily have been memory mapped from disk using `Set::from_path`.

let set1 = Set::from_iter(&["AC/DC", "Aerosmith"])?;

let set2 = Set::from_iter(&["Bob Seger", "Bruce Springsteen"])?;

let set3 = Set::from_iter(&["George Thorogood", "Golden Earring"])?;

let set4 = Set::from_iter(&["Kansas"])?;

let set5 = Set::from_iter(&["Metallica"])?;

// Build our regular expression query.

let spaces = Regex::new(r".*\s.*")?;

// Build a set operation. All we need to do is add a stream from each set and

// ask for the union. (Other operations, such as `intersection`, are also

// available.)

let mut stream =

set::OpBuilder::new()

.add(set1.search(&spaces))

.add(set2.search(&spaces))

.add(set3.search(&spaces))

.add(set4.search(&spaces))

.add(set5.search(&spaces))

.union();

// This is the same as the previous example, except our search narrowed our

// results down a bit.

let mut keys = vec![];

while let Some(key) = stream.next() {

let key = from_utf8(key)?.to_string();

keys.push(key);

}

assert_eq!(keys, vec![

"Bob Seger", "Bruce Springsteen", "George Thorogood", "Golden Earring",

]);Building a set operation works with any type of stream. Some streams might be regular expression queries, others might be Levenshtein queries and still others might be range queries.

This section covers sets, but we’ve left out maps. Maps are somewhat more

complex, because the stream produced by a set operation on the map’s keys must

also include the values associated with each key. In particular, for a union

operation, each key emitted in the stream may have occurred in more than one of

the maps given. I will defer to

fst’s API documentation for a map

union,

which contains an example.

Raw transducers

All of the code examples we’ve seen so far have used either the Set or Map

data types in the fst crate. In fact, there is little of interest in the

implementations of Set or Map, as both of them simply wrap the Fst type.

Indeed, their representation is:

// The Fst type is tucked away in the `raw` sub-module.

use fst::raw::Fst;

// These type declarations define sets and maps as nothing more than structs

// with a single member: an Fst.

pub struct Set(Fst);

pub struct Map(Fst);In other words, the Fst type is where all the action is. For the most part,

building an Fst and querying it follow the same pattern as sets and maps.

Here’s an example:

use fst::raw::{Builder, Fst, Output};

// The Fst type has a separate builder just like sets and maps.

let mut builder = Builder::memory();

builder.insert("bar", 1).unwrap();

builder.insert("baz", 2).unwrap();

builder.insert("foo", 3).unwrap();

// Finish construction and get the raw bytes of the fst.

let fst_bytes = builder.into_inner()?;

// Create an Fst that we can query.

let fst = Fst::from_bytes(fst_bytes)?;

// Basic querying.

assert!(fst.contains_key("foo"));

assert_eq!(fst.get("abc"), None);

// Looking up a value returns an `Output` instead of a `u64`.

// This is the internal representation of an output on a transition.

// The underlying u64 can be accessed with the `value` method.

assert_eq!(fst.get("baz"), Some(Output::new(2)));

// Methods like `stream`, `range` and `search` are also available, which

// function the same way as they do for sets and maps.

If you’ve been following along, this code should look mostly familiar by now.

One key difference is that get returns an Output instead of a u64.

An Output is exposed because it is the internal representation of an output

on a transition in the finite state transducer. If out has type Output,

then one can get the underlying number value by calling out.value().

The key feature of the Fst type is the access it gives you to the underlying

finite state machine. Namely, the Fst type has two important methods

available to you:

root()returns the start state or “node” of the underlying machine.node(addr)returns the state or “node” at the given address.

Nodes provide the ability to traverse all of its transitions and ask whether it

is a final state or not. For example, consider starting a path to trace the key

baz through the machine:

use fst::raw::{Builder, Fst};

let mut builder = Builder::memory();

builder.insert("bar", 1).unwrap();

builder.insert("baz", 2).unwrap();

builder.insert("foo", 3).unwrap();

let fst_bytes = builder.into_inner()?;

let fst = Fst::from_bytes(fst_bytes)?;

// Get the root node of this FST.

let root = fst.root();

// Print the transitions out of the root node in lexicographic order.

// Outputs "b" followed by "f."

for transition in root.transitions() {

println!("{}", transition.inp as char);

}

// Find the position of a transition based on the input.

let i = root.find_input(b'b').unwrap();

// Get the transition.

let trans = root.transition(i);

// Get the node that the transition points to.

let node = fst.node(trans.addr);

// And so on...

With these tools, we can actually show how to implement the contains_key

method!

use fst::raw::Fst;

// The function takes a reference to an Fst and a key and returns true if

// and only if the key is in the Fst.

fn contains_key(fst: &Fst, key: &[u8]) -> bool {

// Start the search at the root node.

let mut node = fst.root();

// Iterate over every byte in the key.

for b in key {

// Look for a transition in this node for this byte.

match node.find_input(*b) {

// If one cannot be found, we can conclude that the key is not

// in this FST and quit early.

None => return false,

// Otherwise, we set the current node to the node that the found

// transition points to. In other words, we "advance" the finite

// state machine.

Some(i) => {

node = fst.node(node.transition_addr(i));

}

}

}

// After we've exhausted the key to look up, it is only in the FST if we

// ended at a final state.

node.is_final()

}And that’s pretty much all there is to it. The

Node type has a few more useful

documented methods

that you may want to peruse.

The FST command line tool

I created the FST command line tool as a way to easily play with data and a demo of how to use the underlying library. I don’t necessarily intend for it to be particularly useful all on its own, but it will do nicely as a way to drive experiments on real data in this blog post.

In this section, I’ll do a very brief overview of the command and then jump right into experiments with real data.

How to get it

Unless you’re dying to play with the tool, it’s not necessary for you to download it. Namely, in this section I’ll usually show the commands I’m running along with their outputs when possible.

Currently, the only way to get the command is to compile it from source. To do that, you will first need to install Rust and Cargo. (The current stable release of Rust will work. The release distribution includes both Rust and Cargo.)

Once Rust is installed, clone the fst repo and build:

$ git clone git://github.com/BurntSushi/fst

$ cd fst

$ cargo build --release --manifest-path ./fst-bin/Cargo.tomlOn my somewhat beefy system, compilation takes a little under a minute.

Once compilation is done, the fst binary will be located at

./fst-bin/target/release/fst.

Brief introduction

The fst command line tool has several commands. Some of them serve a purely

diagnostic role (i.e., “I want to look at a particular state in the underlying

transducer”) while others are more utilitarian. In this article, we’ll focus on

the latter.

Here are the commands:

dot- Outputs an FST to the “dot” format, which can be used by GraphViz to render a visual display of the image. I used this utility to create many of the images in this blog post.fuzzy- Run a fuzzy query based on Levenshtein distance against an FST.grep- Run a regular expression query against an FST.range- Run a range query against an FST.set- Create an ordered set represented by an FST. Its input is simple a list of lines. It takes unsorted data by default, but can build the FST faster when given sorted data and passed the--sortedflag.map- The same asset, except it takes a CSV file, where the first column is the key and the second column is an integer value.

The set and map commands are crucial, because they provide a means to build

FSTs from plain data.

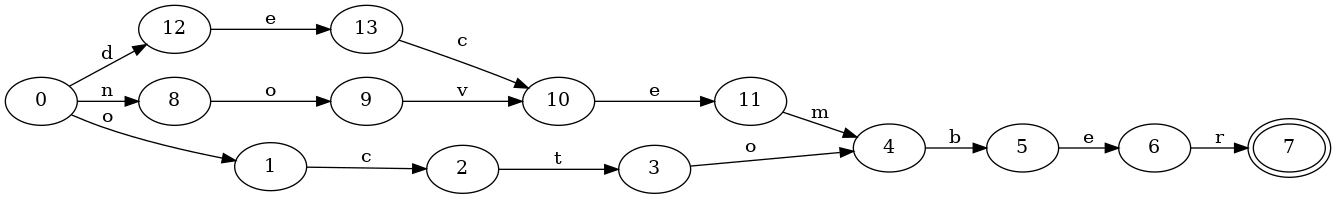

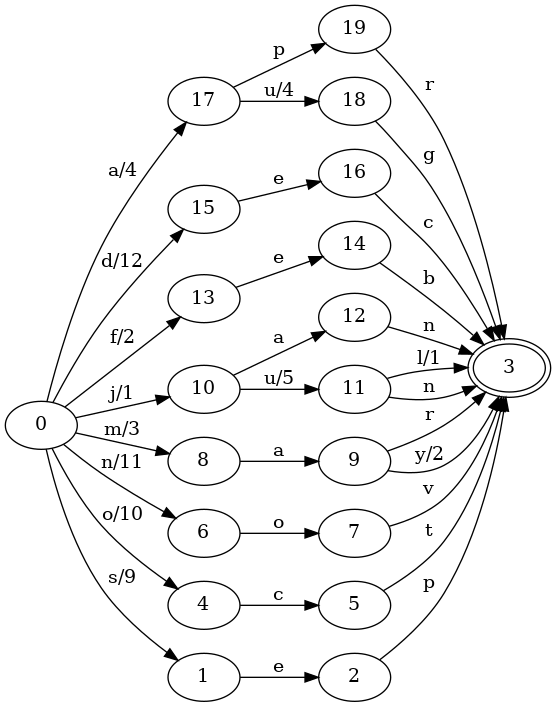

Let’s start with a simple example that we can easily visualize. Consider a map from month abbreviation to its numeric position in the Gregorian calendar. Our raw data is a simple CSV file:

jan,1

feb,2

mar,3

apr,4

may,5

jun,6

jul,7

aug,8

sep,9

oct,10

nov,11

dec,12We can create an ordered map from this data with the fst map command: